(Commodore Matthew C. Perry, c. 1856-1858)

In the 1860’s, Commodore

Matthew C. Perry reopened trade agreements with Japan via diplomatic trips. Ukiyo-e prints flowed into Europe,

especially France. French Impressionistic artists, like Edgar Degas and Henri

Toulouse-Lautrec had quite an appeal for the ukiyo-e prints. This was also due to the imperialism of Europe at

the time. Paris was very much interested in other cultures and new findings.

After two centuries in exile, Japanese art appeared strange and unusual for

Europeans, yet elegant and refined. It became clear that artistic values were a

part of every aspect in the Japanese culture. Europe was experiencing

depressing after effects of the industrial movement. The Japanese spirit refreshed

creative alternatives in Europe at a time when they needed it most.

(Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Self-portrait in the crowd at the Moulin Rouge, 1892-95)

With the increase of urbanization

and print distribution in Japan, an increase in literacy was also prevalent.

After awhile, the roles of collector and scholar were reserved for the wealthy

class and ordinary townsfolk. With the advent of art and literature

combinations, ukiyo-e artist Katsushika Hokusai coined the term manga by publishing and distributing

books with art in them. His book, titled Hokusai

Manga, gained worldwide exposures while simultaneously influencing Western

artists like Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gauguin. The multi-colored,

straightforward, patterned styles of ukiyo-e

prints continue to be expressed in modern day Japanese manga and anime. For

example, manga artists were the first

to depict figures with different colored hair. Ever since then, variations of

eccentric hair colors have inundated itself into the dominant population of

citizens with black hair color. It is also more common that the youth will

mimic manga than the older

generations. The first artists to experiment with Japanese animation were the manga artists themselves. They

considered it to be an extenuation of the

manga print, but in moving form. Known as anime, these Japanese animations required smaller budgets than live

action movies, and garnered the same fan base as their manga counterparts.

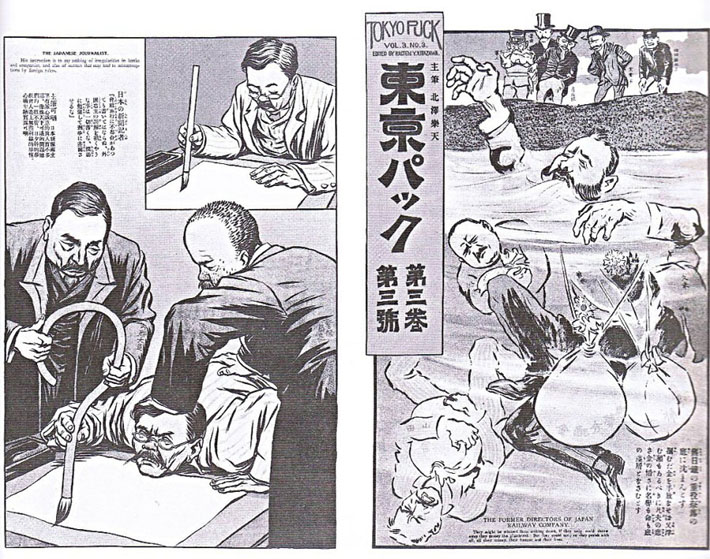

(Rakuten Kitazawa, Tokyo Puck

Magazine Vol. 3, 1905)